How the AI race is moving to the physical world

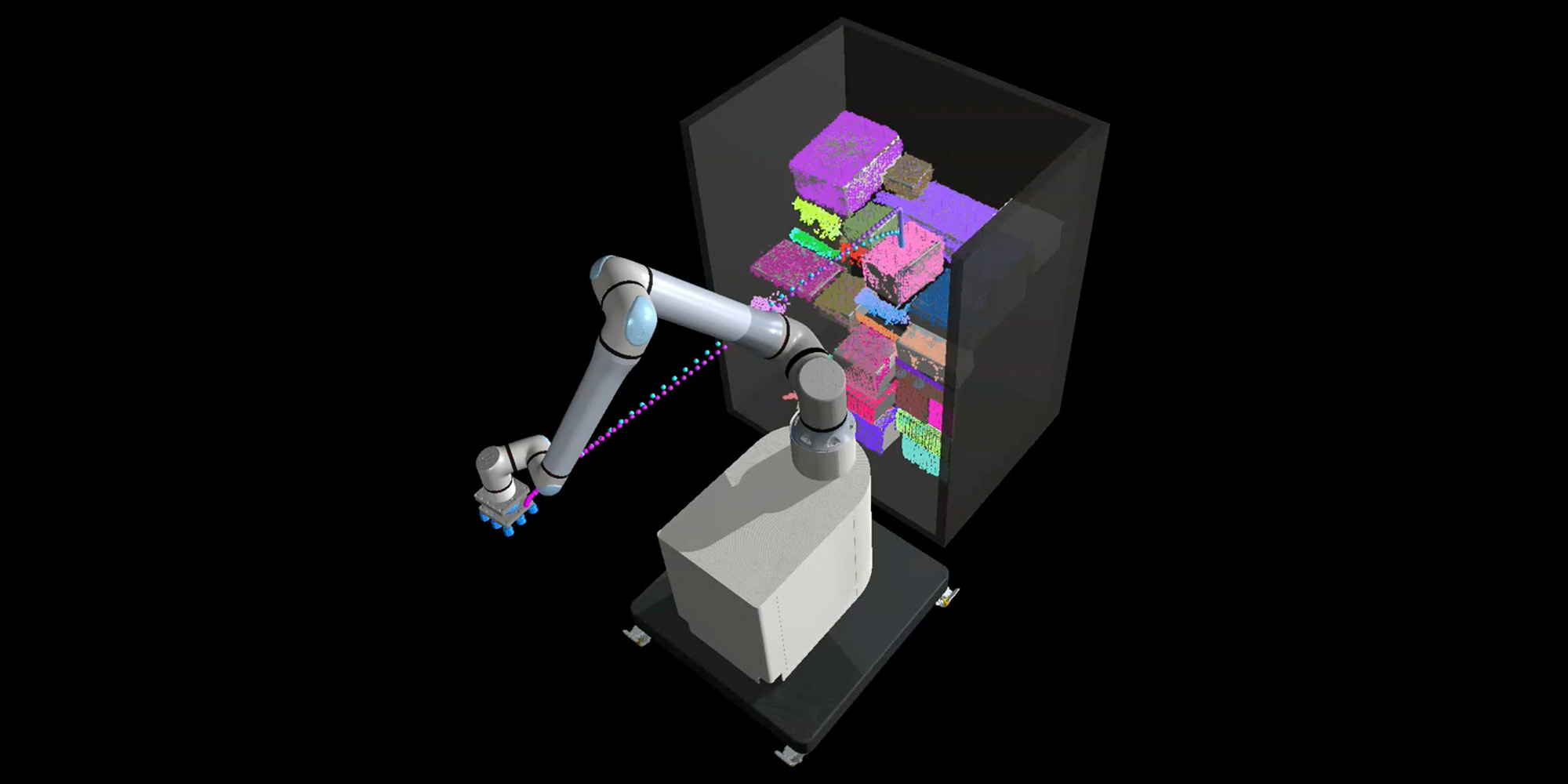

That evolution is physical intelligence - built on three core capabilities: perception, planning, and action. To act reliably in the real world, robots must build a digital twin of reality with sensors and computer vision, decide how to move by “trying out” thousands of possible trajectories, and then physically execute said plan in real time. The foundations for physical intelligence are differentiable physics engines, that ensure predictions in the digital twin match real execution.

To interact with the real world, the robot needs to correct its actions several hundred times per second, plan new motions within fractions of a second, and update the digital twin at least a dozen times per second. Each of these tasks is complex on its own; the greater challenge is making them work together through a tight feedback loop - an absolute necessity for real world impact. To prove itself useful, physical intelligence also needs to be rolled-out at scale within productive operations.

The transition from the lab to operations has been difficult: few robots are successful. The most effective robots to date have been domain-specific. Robotic vacuum cleaners are a great example: They function in unstructured environments but their task is highly repetitive and this allowed early models to deliver immediate productivity gains. This enabled manufacturers to learn faster than competitors who remained in the lab. That foothold mattered: ‘on the ground’ they improved quickly, expanding to tasks such as obstacle detection, home monitoring, and wet cleaning. A focused, solvable starting point made fast development possible.

Logistics offers the same foundation but with greater operational demand. It has defined limits - weights, dimensions, materials - yet enough variability in objects and surroundings to push the limit of intelligent robotics. For workflows such as bulk singulation and unloading, robots can already outperform manual handling in consistency and endurance. Every extraction, placement, and correction strengthens the underlying models. Shared data across tasks accelerates generalisation. Deployment speed becomes learning speed.

This is the reasoning behind the Flink approach - instead of building new hardware for each workflow, we developed one machine that handles multiple use cases. Flinkbot, our broad purpose logistics robot, can be deployed fast and enables a single learning loop across all use cases.

In AI-driven systems, the ability to learn faster directly translates into building better products and ultimately, into competitive advantage.

Join the team

physical work, for anyone, anywhere.